UK-EU anti-trafficking cooperation after Brexit

In this new guest post on our blog, Clara Cotroneo shares her insights into UK-EU anti-trafficking cooperation after Brexit. Ms Cotroneo is a lecturer, researcher, and doctoral candidate at the University of Leiden’s Institute of Security and Global Affairs. She also works as a full-time Senior Consultant for ICF, and is based in Brussels.

Media and political debates in Europe have been increasingly discussing the impact of the UK’s exit from the European Union (Brexit) on trafficking in human beings (THB). The frequency with which this topic appears in public debates is not surprising, given that trafficking is often associated with undocumented migration; that migration control – ‘taking back control of our borders’ – has been one of the leitmotifs of the Brexit campaign and the subject of newly tabled migration policies in the UK; and that reports of undocumented migrants who attempt at crossing the Channel have become more frequent. To clarify the terminology used here, ‘THB’ – a term often misused and merged together with migrant smuggling – is a distinct crime which may – or may not – involve undocumented border crossing. There are fundamental differences between ‘people smuggling’ and ‘human trafficking’ both in terms of what each entails from a criminal law perspective, and in terms of the experiences of victims. ‘Migrant smuggling’, as a crime, involves the facilitation of illegal entry of a person in a country in which they have no legal right to enter or stay, in return for a payment. THB, on the other hand, involves the movement, receipt of harbouring of adults and children for the purpose of exploitation, across different industries. Some cases THB may start as smuggling, however this is not always the case and THB does not need movement or cross-border passing to take place.

Since the announcement of the Brexit referendum, concerns have been raised over the impact that Brexit would have on THB, on whether the work of traffickers would be easier and that of law enforcement and judicial agencies harder, and whether there would be greater risk for some vulnerable groups, including asylum seekers and EU workers. The International, EU and UK anti-Trafficking legal and operational frameworks taken together propose a victim-centred approach to THB, and four key pillars for anti-trafficking: Prevention, Protection, Prosecution and a cross-pillar, Partnership. All of these pillars working in continuum together and in partnership – i.e., through cross-border collaboration – is both a necessary condition for ‘good’ anti-trafficking, and one of the goals of the international anti-trafficking framework. This is because cross-border cooperation can help keep in check both domestic and cross-border trafficking.

When the UK was a member of the EU, the two blocks could rely on advanced and sophisticated instruments to support their individual and joint efforts against cross-border organized crime, including THB. Full participation in law enforcement and judicial cooperation agencies (EUROPOL and EUROJUST), common access to EU databases (e.g., SIS II) and the sharing of a common legislative framework and instruments, such as the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) and the European Investigation Order (EIO) made it possible to go beyond intergovernmental cooperation and have common grounds on mutual assistance. Such arrangements could be maintained while the UK could still select, à la carte, in which EU instruments to participate. The question, therefore, is whether in a still uncertain and largely undefined security cooperation arrangement, UK and EU law enforcement and judicial agencies will now have the same capacity to cooperate against THB. A hampered cooperation between security and intelligence communities could potentially result in higher vulnerabilities and cases of THB.

Intelligence-sharing in anti-trafficking

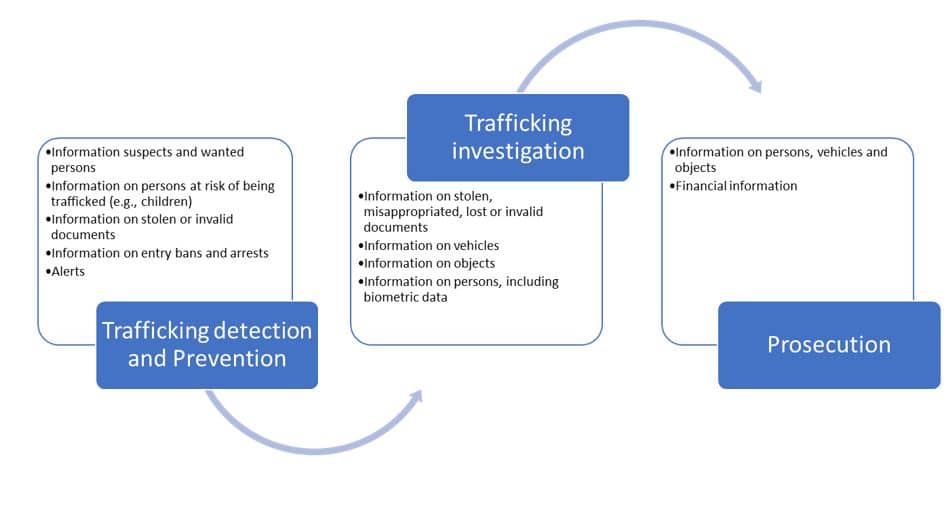

Criminal records, intelligence and analytical insights related to trafficking crimes are undoubtedly a trump card in the hands of law enforcement and prosecuting authorities. These can help with crime prevention, identification, prosecution and management. Rather than providing an extensive overview of all the tools that the UK- and EU have used for the exchange of criminal intelligence, data and insights, in this post I will focus on one case study which will allow us to understand the potential pitfalls that Brexit may have on anti-trafficking in Europe. The Schengen Information System II (second generation) is one of the largest and most used databases for detecting and preventing cross-border crime in Europe. While useful to detect and prevent a number of cross-border crimes, the figure here below provides an overview of those functionalities of this system that are relevant to anti-trafficking in particular.

The systems allows law enforcement authorities – including police and border officers, to do the following:

- Input data relevant to anti-trafficking investigations, and other domestic and cross-border crimes

- Input and receive ‘alerts’: these are sets of instructions for officers in other jurisdictions on what they should do if they come across individuals (for example, suspects or missing persons) or objects (for example, fraudulent documents)

- Exchange data with competent law enforcement and judicial authorities for the purpose of crime investigation and prosecution.

The SIS II has therefore direct relevance to anti-trafficking. Police officers and border guards can find information on children who may be abducted, detect cases of trafficking difficult to spot otherwise – for example, because the victim is an adult travelling with valid documents – and extrapolate information for big data analysis to identify and predict trends.. Therefore, in the field of anti-trafficking, this database is an optimal example to better appreciate the wealth of data that can be exchanged, the speed at which they can be exchanged and the competitive advantage that information-exchange gives to law enforcement against traffickers.

There are 30 European countries currently participating in the SIS II. These include all EU Member States, excluding Ireland and Cyprus, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland (all Schengen countries). Unfortunately, as the UK has never been part of the Schengen Area and therefore, with them no longer part of the EU, the exchange of information through SIS II will no longer be possible.

Conclusions, limitations and opportunities for policy-makers

We took one case study in particular to provide detailed mapping and practice-oriented insights of the functions that EU databases have for combating THB. Breaking links and cooperation opportunities between EU and UK law enforcement can have a profound impact on potential and current victims of trafficking crimes. It can accelerate the recruitment of new victims and hamper efforts to identify and rescue current victims. The collaborative efforts of law enforcement authorities are important for the protection of the rights of victims of trafficking and for the prevention of further violations and abuses. The collaborative efforts of judicial authorities are fundamental not only for bringing perpetrators to justice, but also for bringing justice to victims, in the form of prosecution as well as through compensation.